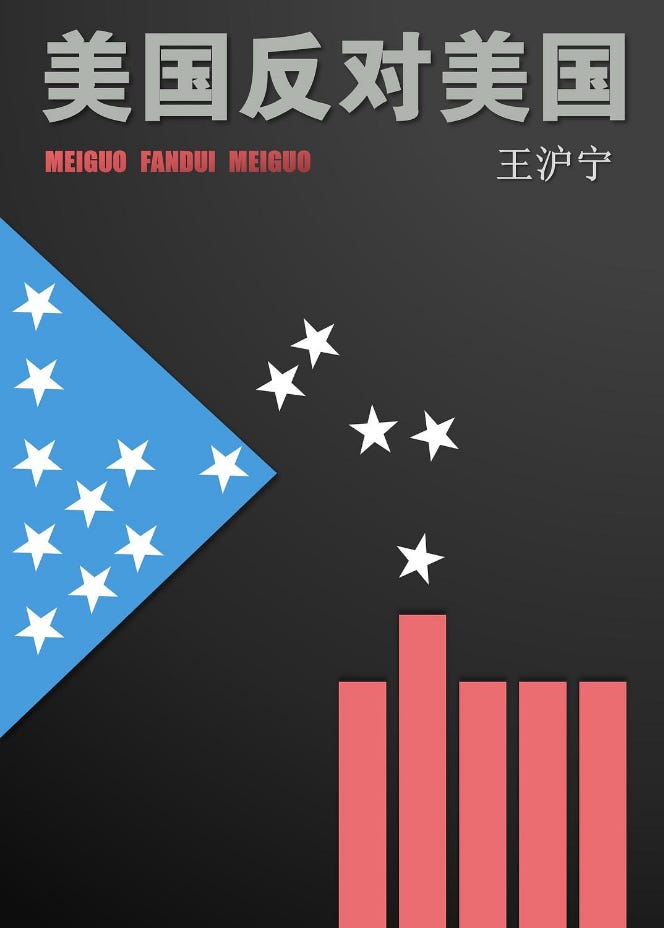

Wang Huning on the Dangers of American Technology

China's Ideologue-in-Chief Critiques American Society

Wang Huning, fourth ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee and China’s ideologue-in-chief, argues that American technology is the foundation of American power. But when he traveled across the United States as a young man Wang concluded that there is a dark side to scientific progress. Wang Huning describes America as a land where millions of men and women willingly surrender their freedom to technological processes that they believe operate beyond their control. In the United States, it is “not man that masters technology, but technology that masters man.”

As part of a larger project examining Chinese thinking on the relationship between technology and national power, the Center for Strategic Translation has published several excerpts from Wang Huning’s 1991 philosophical travelogue, America Against America. In November we published a general introduction to the book, as well as passages from the book that explore the connections between American technology and American might and passages that investigate the cultural foundations of American science and technology. We have now published two new excerpts from America Against America, each a critique of technology’s role in American life:

“The Space Shuttle Misdirection” and “Technology Governs Man.”

Wang Huning believes that Americans’ most abiding faith is in science and technology. There is no authority that Americans trust more. To every social, ethical, or political problem the American first seeks a technical or scientific solution. However:

These beliefs can also have an alienating effect. These beliefs have led Americans to come up with numerous ways to resolve the problems they face, the result being a high degree of scientific and technological development. However, with great scientific and technological development also comes an illusion: it seems that the agent ultimately solving a difficult problem is not human; rather, science and technology become the ultimate power while man becomes their slave.

In contrast to Tocqueville’s America, where there was “nothing the human will despairs of attaining through the free action of the combined powers of individuals,” Wang’s America does not operate through the combined powers of individual Americans. What matters is the relationship between the individual and the machine:

Automation and electronification cause every person to complete their designated work in their designated position with no need to depend on other humans, or to obey the commands of another human. They only need to depend on a machine; the only commands they obey are that of a machine.

Advanced economies require specialized labor and technical knowledge to function. These processes themselves function like great machines with people serving as their cogs and gears. Even highly trained individuals are reduced to a node on a flow chart:

Applying science and technology–especially advanced technology–in a particular manufacturing process requires splitting this process into innumerable parts…. [Therefore] techno-scientific development fragments society into small, interconnected nodes, with each person occupying their own node in the chain. Entering a node requires specialized technical expertise.

Wang sees benefits to this process in terms of public order. He worries, however, at the social and political consequences of surrendering human choice to non-human structures. Wang uses words like “illusion” and “misdirection” to describe what is happening. America still has political maneuvers, economic planning, and other forms of conscious decision making. But the logic of science and technology obscures how and why these decisions occur. Science lies outside the realm of human choice or human values. Americans conceive of technical challenges much like math problems—a class of problems whose solutions follows naturally and inevitably from their premises. However, treating a chosen policy as scientific, value-neutral, and apolitical does not make it apolitical or value-neutral. “It may take generations,” Wang concludes, “for Americans to recognize this misdirection.”

To “overtake the Americans,” Wang argues, “one thing must be done: surpass them in science and technology.” The implicit question posed in these passages is whether China can overtake modern American technology without technology making China too much like modern America.

Certainly the Communist Party of China is attempting this task. It is not hard to trace connections between Wang’s 1991 musings and the concrete policies crafted in the age of Xi Jinping. Wang’s fear that modern men are too easily dominated by their own creations are similar to the anxieties that prompted the 2021 crackdown on digital algorithims, video gaming, online fandoms, and other tech monopolies. Xi Jinping’s decade long struggle to inject ‘red’ consciousness into a Party teetering towards technocracy align with Wang’s worries about the consequences of apolitical administration. The Communist Party of China aims to govern technology instead of be governed by it.

Read the full translation of these passages here HERE.

Coming Soon

The Center for Strategic Translation will continue its investigation of the roots of Chinese techno-nationalism in the weeks to come. We will soon publish a final excerpt from America Against America (“The Furnace of Technology”), as well as a CICIR study on the role that technology has played in the last 500 years of “the rise and fall of great powers.”